Espinoza: a Good Decision That Will Produce Some Bad Results

July 8, 2020

Cathy Duffy

Most conservatives are elated about the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Espinoza vs. Montana Department of Revenue. The decision struck down the state’s law that prohibited any type of aid from the government to religious schools. On one hand, this is a decision worth celebrating. On the other hand, it could end up destroying the nature of private religious schools.

Background

Prohibitions against government funding of religious schools are rooted in the anti-Catholic bigotry of the nineteenth century. Alarmed by the large numbers of Catholic immigrants and the rapidly growing network of Catholic schools, Republican Congressman James G. Blaine proposed an amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1875 which said, “no money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefor, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect; nor shall any money so raised or lands so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations.” Anti-Catholic, nativist sentiment was strong, so even though Blaine failed at the federal level, 38 states adopted some form of this language into their own constitutions. Ever since then, these so-called “Blaine amendments” have been used as a means of restricting government money from finding its way into private religious schools.

In the Espinoza case, money had been funneled through a tax-credit program for private-school scholarships in Montana. Taxpayers could get a credit against state taxes owed by donating to a private-school scholarship fund. Those running the fund could then award scholarships to children to help them attend either secular or religious private schools. Kendra Espinoza and other parents were able to take advantage of the program to receive scholarships which they used at private religious schools. The Montana Department of Revenue decided that parents could not use the scholarships at religious schools. The families sued. The Montana Supreme Court upheld the decision of the Department of Revenue, and in an odd twist, said that the entire scholarship program had to be scrapped. The case then ended up at the U.S. Supreme Court where the decision upheld the right of religious schools to participate in the tax-credit scholarship program. With the Montana Supreme Court’s decision invalidated, it remains to be seen what happens next with state’s program.

According to Educational Choice, a leader in the school-choice movement, 18 states have tax-credit scholarship programs that allow students to attend private religious schools. Some of these programs have already prevailed against legal challenges. The Espinoza decision at the U.S. Supreme Court now provides strong legal grounding for all existing programs and for potential new programs in all states. These include tax-credit scholarship programs, vouchers, charter schools, and education savings accounts.

Advocates for School Choice Promote More Programs

Conservative groups, particularly those groups advocating school choice, are celebrating the Supreme Court decision and preparing to advance school choice programs across the country. A typical example of this is the Center for Education Reform (CER), which wrote: “The Espinoza victory represents monumental progress toward reversing damage that has been done for nearly 150 years and which states can now address.” Jeanne Allen, founder and chief executive of the CER said, “For many families, Espinoza not only provides the potential for expanded opportunities for them to educate their children, including the choice of religious education, but also the right to decide what they believe is the most effective way to do so.” (“U.S. Supreme Court Validates Parents’ Rights”)

The American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), predicting in advance a decision in favor of Espinoza, had already launched their “School Choice Initiative” before the decision came down. They said,

At the ACLJ, we have launched our School Choice Initiative to ensure that every state in the country allows parents to choose the school they believe will provide their kids the best education – whether it’s a private, religious, charter, homeschool, or public school – regardless of economic standing.

We are drafting model state legislation to ensure that every child has equality of opportunity in education, including school vouchers.

Critics and Demands for Accountability

Meanwhile, critics of school choice, such as the National Education Association, have complained about the lack of accountability for schools participating in tax-credit scholarship programs such as Montana’s. These critics overlook the fact that parents are strongly motivated to choose a good school for their own children, and they display a mistrust of parents’ ability to choose wisely. Criticisms of school choice also reveal a deeper animus (such as that expressed by American United for Separation of Church and State) against private religious schools in general because they can integrate faith-based instruction throughout the curriculum and make hiring decisions based upon religious beliefs.

To answer critics’ concerns about accountability for educational results, many school choice programs require private schools to administer state-approved tests. In effect, this gives the state control over the religious schools’ curricula to an extent that varies according to the approved tests and how tightly those tests are aligned with any particular curriculum. And therein lies part of the problem.

Loss of Control for Participating Private Schools

Many private schools follow a curriculum that does not align with that of public schools, so students in private and public schools are often not learning the same things at the same time. Requiring private schools to use a test designed for a different curriculum puts them at a disadvantage. The pressure on private schools to produce good test results can force them to redesign their curriculum─in effect making them more similar to their public school counterparts. Private schools, especially religious schools, can easily drift away from their original mission and vision to keep the money that results from increased enrollment.

Religious schools are often subsidized by a church and struggle to keep the tuition affordable, so they are often eager to take advantage of ways to increase the enrollment of students with guaranteed funding from school choice programs. In addition, religious schools are often more vulnerable to pressures to change their curricula than others because they are more likely to have religious content throughout the curriculum as well as content that doesn’t align with what is being taught in public schools.

Vouchers programs in 14 states and the District of Columbia are more problematic than tax-credit scholarship programs because the money flows more directly to the schools. This invites even greater control than that exerted by tests. For instance, the Milwaukee Parental Choice program, the first such voucher program in the country, has extensive regulations that apply to participating schools─regulations about accreditation, teacher qualifications, hours of instruction, and testing among many others. They must submit a budget and be audited annually. One of the most significant regulations is that they must accept students on a random basis. Religious schools cannot show a preference for students who share their religious beliefs, and students are allowed to opt out of any religious activities. So one must ask, “How many students can a religious school enroll who don’t support the church’s mission, don’t receive any religious education, and don’t participate in religious activity before you have changed the very nature of the school?”

But government regulation of religious schools seems irrelevant to conservative organizations promoting vouchers. ACLJ is only one of a number of such organizations. Referring to the variety of school-choice options, CER’s Jeanne Allen wrote, “Many of these impressive programs provide tax credits and third-party scholarships to families making choices difficult to navigate and often difficult to afford. They are great programs, all of them, and provide parents with some to lots of power. However real power for parents comes from having direct purchasing power in the form of vouchers.”

Even though vouchers invite greater regulation, school choice advocates favor them because they generally cover the full amount of the private school’s tuition while tax-credit scholarship programs generally fund only a portion of the tuition.

Harm to Private Religious Schools

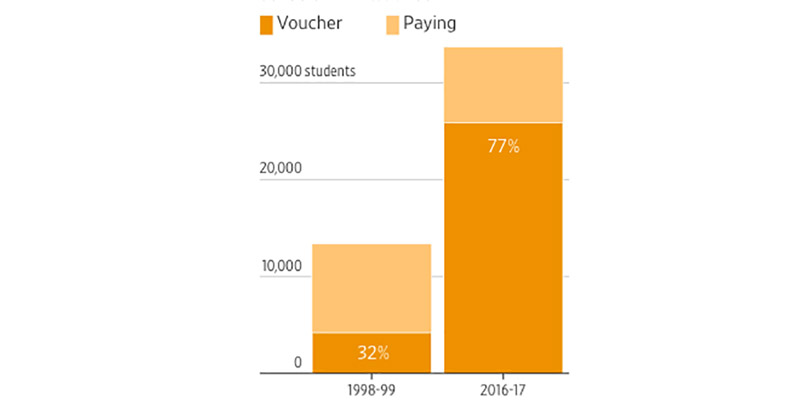

According to an analysis by The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), in the 2016-2017 school year in Milwaukee, 109 of the 120 voucher-receiving schools were religious. Since the voucher program began in 1990, the percentage of voucher receiving students has gradually crept up at most of these schools. (There was a surge beginning in 1998-99 when religious schools were allowed to participate.) The graph below (from the same WSJ analysis) shows the overall number of voucher students compared to paying students at the voucher-receiving schools, comparing the 1998-99 and 2016-17 school years. A few schools limit the number of voucher-receiving students, but 81 of the 120 schools in the study had at least 75% of students receiving vouchers.

Maybe religious schools can survive government regulation, but they’ll find it hard to survive the loss of their religious character. When the large majority of a school’s students are on vouchers, and the school has not been able to select those who support the school’s religious perspective, the religious mission of the school will be undermined by lack of both parent and student support.

Milwaukee’s religious schools were suffering enrollment declines prior to the availability of vouchers. Now they have the income they need to function, but they have sacrificed their mission.

Voucher-receiving schools cannot require information about the religious affiliations of their students. Since we don’t have direct information about the faith of students, we can only use the secondary effects that we see at the church or parish level to judge the effect of vouchers on the religious character of a school and its associated church.

According to research from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) that focused on 71 Catholic parishes, vouchers have kept religious schools and their parishes alive, but at a tremendous cost. In the abstract for this research they summarize:

We show that vouchers are now a dominant source of funding for many churches; parishes in our sample running voucher-accepting schools get more revenue from vouchers than from worshipers. We also find that voucher expansion prevents church closures and mergers.

Despite these results, we fail to find evidence that vouchers promote religious behavior: voucher expansion causes significant declines in church donations and church spending on noneducational religious purposes. The meteoric growth of vouchers appears to offer financial stability for congregations while at the same time diminishing their religious activities.

The body of the paper details what this means for Catholic parishes. Vouchers cause a significant decrease in spending on non-school religious purposes such as religious staff salaries, mission support, and church maintenance. Church donations decrease dramatically. The study points out: “[O]ur numbers suggest that, within our sample alone, the Milwaukee voucher program has led over time to a decline in non-educational church revenue of $60 million.”

If the reason for the existence of Catholic schools is to promote the mission of the church, the study shows that vouchers work against that goal. The authors summarize: “Overall, the results repeatedly refute the possibility that vouchers subsidize or otherwise promote greater religious activity or vitality within recipient parishes. Indeed, the results suggest the opposite. In particular, looking at expenditures on non-school religious activities, we repeatedly find robust evidence that vouchers decrease parish religious activity.”

The study’s authors point out the bottom line: “The ‘effect’ of vouchers on religion depends upon whether one characterizes religion by the prevalence of churches or by the activities within churches.” The income from vouchers keeps struggling Catholic parishes from having to merge, which most Catholics would consider a good thing, but the cost of doing so is a decrease in their focus on their religious mission.

Some voucher advocates might say that educating children is a sufficient goal in itself no matter the effect on religiosity. But the NBER study shows that “the bulk of those [schools] with the highest voucher enrollments fall in the bottom quartiles of private schools for results on state exams, which voucher students are required to take.” In general, the quality of the education provided by private schools as judged by educational results decreases as the proportion of voucher students increases. Some private schools deliberately cap the number of voucher students to try to prevent this from becoming a significant problem.

We’ve had many years to study Milwaukee, and the results are dismaying. Even if a school choice advocate’s only goal is to remove children from public schools and put them into another institution, vouchers gradually reshape private schools so that they start to resemble the public schools from which the children were “rescued.”

The harm done to the Catholic schools and parishes in Milwaukee is an indicator that vouchers can kill the goose that lays the golden egg. Catholic schools have historically done an excellent job of educating their students─often inner-city minority children. Most have done so while also furthering the mission of the Catholic Church. Vouchers have damaged both the educational and religious mission of Catholic schools.

While I have focused particularly on Catholic schools in Milwaukee since this is the largest and oldest voucher program, a broader study of voucher programs in Washington DC, Indiana, and Louisiana discovered a homogenizing effect on private schools in the most heavily regulated voucher programs. The report says,

Some of the voucher program regulations, such as financial reporting and auditing, may not impose large costs on participating private schools. Others, however, may inadvertently change the overall mission, strategy, and composition of private schools. Costly conditions tied to funding include standardized testing requirements, open-admissions processes, teacher certification requirements, and the prohibition of parental copayment.

This research was done in 2017 by Corey A. DeAngelis from the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas and who also serves as a policy analyst for the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, organizations that are in favor of school choice. In his conclusion, DeAngelis warns:

Since private school choice programs are being proposed in several locations across the United States, decision-makers ought to pay close attention to policy design. While additional regulations often appear beneficial, especially since they give policy-makers the illusion of control, costs of program participation can lead to unintended consequences for children. Our estimates indicate that additional regulations could reduce specialization in the supply of schooling, and, as a result, fewer choices for families. If the diverse backgrounds, interests, and abilities of children are not matched with the available institutions, educational choice programs could fail to lead to improved outcomes.

Opposition to School Choice = Defense for Private Schools

Following the Espinoza vs. Montana Department of Revenue decision, forces are aligning primarily on only two sides of the school choice issue. School choice proponents want more government funding for private schools. Meanwhile, school choice adversaries will continue the resistance they have exhibited for decades, while also advocating for increased regulation for school choice programs.

Some of us do not align with either of those two camps. We object to school choice programs, not because we are fans of government schools, but because we doubt the ability of private religious schools to maintain their freedom and their unique character if they accept government funding.

Frank Chodorov wrote in Why Free Schools Are Not Free:

The more subsidized it is, the less free it is. What is known as “free education” is the least free of all, for it is a state-owned institution; it is socialized education – just like socialized medicine or the socialized post office – and cannot possibly be separated from political control.

Whether that funding of education is direct or indirect, the end result will likely be the same.